Water scarcity is becoming one of the defining global challenges of the 21st century. Hotter climates, over-exploited aquifers, growing populations and rising agricultural demand are putting unprecedented pressure on water systems. At the same time, new technologies—solar pumping, desalination, atmospheric water generators (AWGs), smart irrigation—are being deployed rapidly, but often without integrated planning. The result is a fragmented landscape where energy, water and infrastructure decisions are made in isolation.

Quantum technologies offer a new toolbox to address this complexity. While still emerging, quantum computing and quantum sensing provide powerful capabilities that complement classical engineering and optimisation methods. Together, they can help governments, utilities, NGOs and large landowners design more efficient, reliable and sustainable water systems.

This article explains how these technologies work, where they can be applied, and why they matter for regions facing water stress.

Why Water Management Needs New Approaches

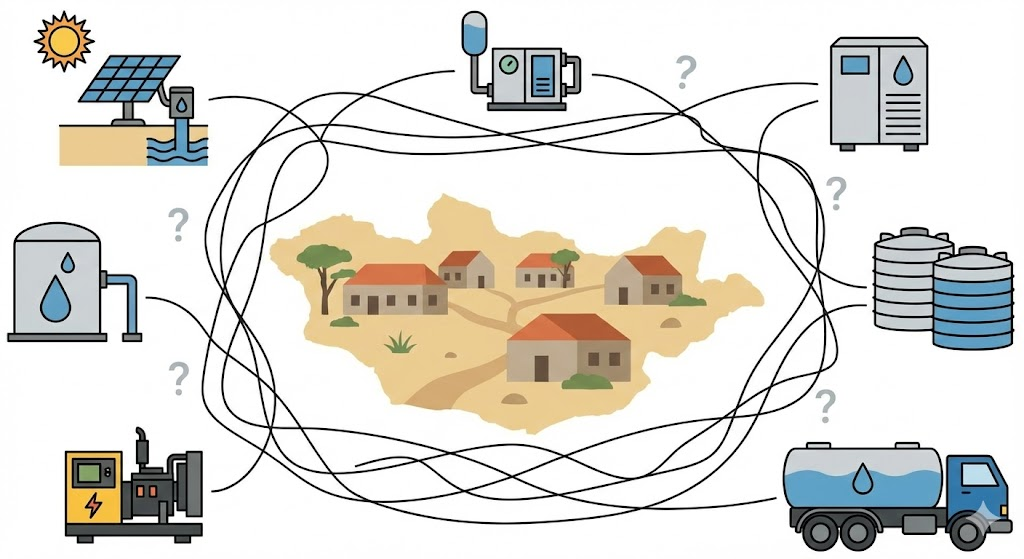

Modern water systems are more complex than ever. A single village, farm or island may combine:

- solar pumps

- desalination units

- atmospheric water generators (AWGs)

- diesel backup

- water tanks and pipelines

- variable irrigation or domestic demand

Optimising these systems is already challenging at the site level.

But the real difficulty appears at the regional scale: dozens of sites share the same aquifers, budgets, infrastructure, fuel supply and climate risks. Planning where to install AWGs or desalination, how to size solar plants, how to operate pumps, and how to allocate limited water resources becomes a complex optimisation problem that classical tools struggle to solve efficiently.

This is exactly where quantum technologies enter the picture.

Quantum Computing for Water Management

Quantum computing is not a faster version of a traditional computer. It is a completely different way of solving complex optimisation problems by exploring many possible configurations at the same time.

Why this matters for water systems

Designing or operating a water network often requires solving high-dimensional questions like:

- Where should AWGs, desalination units and solar systems be installed first?

- What is the best sizing strategy for PV and storage across dozens of locations?

- How should pumping and irrigation be scheduled under drought scenarios?

- How do we maximise water security while minimising energy and diesel use?

These are NP-hard optimisation problems, similar to the “Travelling Salesman Problem.” As the number of sites, technologies and scenarios grows, the number of combinations explodes. Classical computers can solve small and medium cases well, but regional-scale planning rapidly becomes computationally expensive.

What quantum computing can do

Quantum computers are well-suited for:

- multi-site optimisation (e.g., 50–500 villages or farms)

- infrastructure placement (where to put AWG, desalisation, PV, storage)

- capacity planning (how big each system should be)

- scenario analysis (drought years, energy prices, groundwater depletion)

- complex scheduling and resource allocation

Hybrid approaches—classical solvers + quantum heuristic layers—can explore more combinations, uncover better configurations, and generate more robust plans.

Importantly, quantum computing is usually accessed through the cloud. No special hardware is installed on-site; the user receives results like any other optimisation report.

Quantum Sensing for Groundwater and Resource Planning

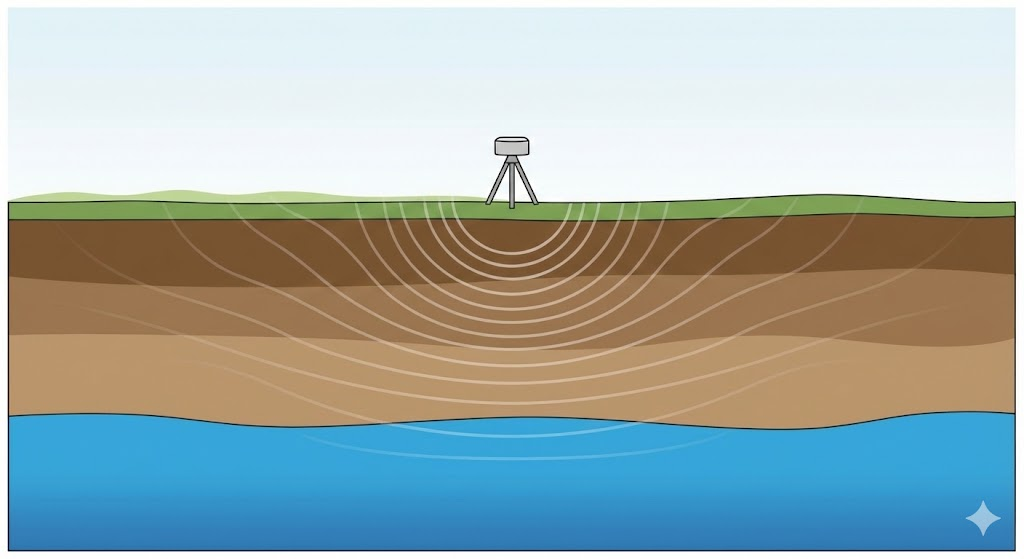

Quantum sensing uses quantum effects to create highly sensitive instruments capable of detecting extremely small changes in gravity or magnetic fields. For water management, the most relevant applications include:

1. Groundwater detection and monitoring

Quantum gravimeters can:

- identify underground water bodies

- track aquifer changes over time

- improve estimates of groundwater availability

- reduce uncertainty in drilling decisions

This is critical for regions where groundwater is the main water source but is poorly mapped.

2. Subsurface characterisation

Quantum magnetometers and gravimeters can help detect:

- soil moisture patterns

- subsurface voids or geological structures

- early signs of over-extraction

Better data enables smarter planning and reduces the risk of system failures.

3. Infrastructure monitoring

Quantum sensors can also support:

- leak detection in pipelines

- structural health monitoring of dams, tanks or desalination facilities

While not yet widespread, these technologies are rapidly maturing.

Key Applications of Quantum Technologies in Water Management

Here are the main areas where quantum computing and sensing add real value:

1. Optimal Deployment of Water Technologies

For AWGs, desalination units, solar pumps and storage systems:

- determine which locations should receive which technology

- calculate optimal sizing

- plan rollout sequences under budget constraints

2. Energy–Water System Optimisation

Integrating water assets with renewable energy:

- minimise energy consumption (kWh/m³)

- reduce diesel and trucked water

- ensure reliability under extreme weather

3. Smart Irrigation and Agricultural Planning

Quantum-enhanced optimisation can support:

- precision irrigation schedules

- crop-water planning

- seasonal water distribution

4. Groundwater Management with Better Data

Using quantum sensing data to:

- map aquifer capacity

- set sustainable extraction limits

- protect groundwater for communities and agriculture

5. Multi-Site Resilience and Drought Planning

Quantifying and improving regional resilience:

- drought-response strategies

- demand-scenario simulations

- fair and efficient water allocation between villages, farms or districts

Why Quantum Technologies Matter Now

Water scarcity is accelerating, but hardware solutions alone (solar pumps, desalination, AWGs) cannot solve the problem without intelligent planning and optimisation.

Quantum technologies provide:

- better decisions, not just better devices

- more robust plans under uncertainty

- more efficient use of limited water and energy resources

- improved resilience for communities and agriculture

They complement classical engineering, helping policymakers and organisations move beyond fragmented, site-by-site planning toward coordinated, resource-efficient strategies.