Optimization is the art of making the best decision under constraints: limited budget, limited capacity, time windows, regulations, risk limits, or resource availability. It shows up in routing, scheduling, production planning, energy systems, and finance.

Quantum computing often gets mentioned as “the next big accelerator” for optimization. The reality is more specific: quantum optimization may help for certain hard combinatorial problems, but classical optimization is already excellent for most real-world cases. If you want a practical view of quantum computing optimization, start with one question:

Is your bottleneck the math (combinatorial complexity), or everything else (data, modeling, integration, operations)?

What is quantum optimization?

Quantum optimization is the use of quantum computers (or quantum-inspired methods) to find good solutions to optimisation problems, especially combinatorial optimization where decisions are discrete (yes/no, pick/not pick, assign/not assign).

Most business optimization decisions can be expressed using binary variables (0/1). Quantum optimization approaches typically target problems that can be written in forms like:

- QUBO (Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization)

- Ising models

- Gate-model approaches often discussed in the context of QAOA-like methods

In practice today, most “quantum optimization” work is hybrid optimization: classical systems run the pipeline, and the quantum part is used as a candidate generator or sub-solver.

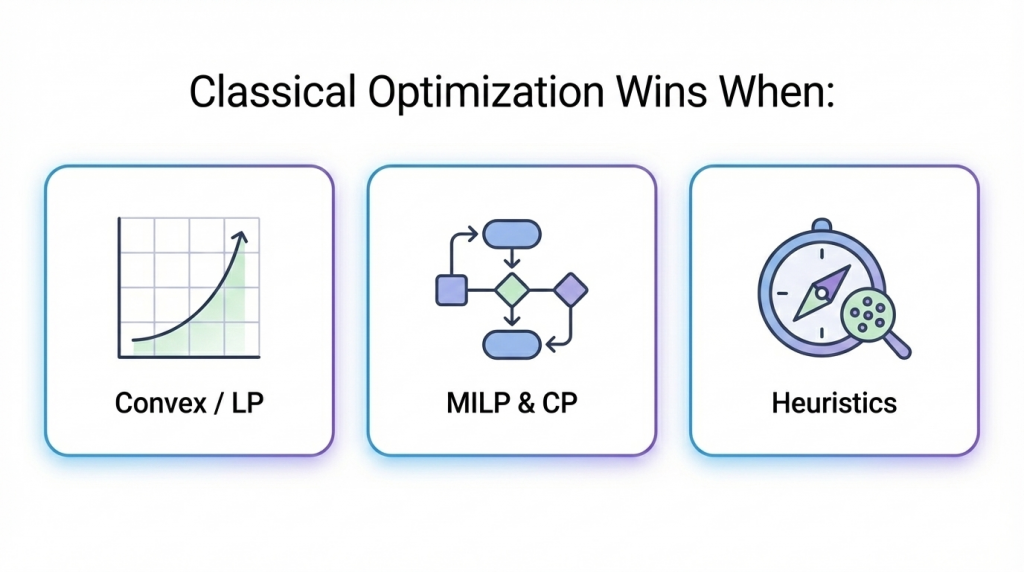

When classical optimization is enough (no quantum needed)

For many organizations, the biggest performance gains come from classical methods plus better modeling. Classical optimization is strong, mature, and production-ready.

Classical approaches that already win in industry

- Linear / convex optimization: extremely fast and reliable when your model is convex (or close enough).

- MILP (Mixed-Integer Linear Programming): the industrial workhorse for routing variants, scheduling, allocation, planning.

- Constraint Programming (CP): excellent for complex scheduling rules and constraints.

- Heuristics and metaheuristics: often deliver high-quality solutions quickly when “near-optimal” is good enough.

Clear signs you do not need quantum optimization

- Your solver finds acceptable solutions in seconds or minutes.

- The real problems are data quality, changing requirements, or unclear objectives.

- Constraints are frequently wrong, missing, or inconsistent.

- The business cannot operationalize the outputs (process, ownership, integration).

If your optimization pipeline is not stable and trusted, adding a quantum component usually adds complexity without ROI.

Where quantum optimization may help

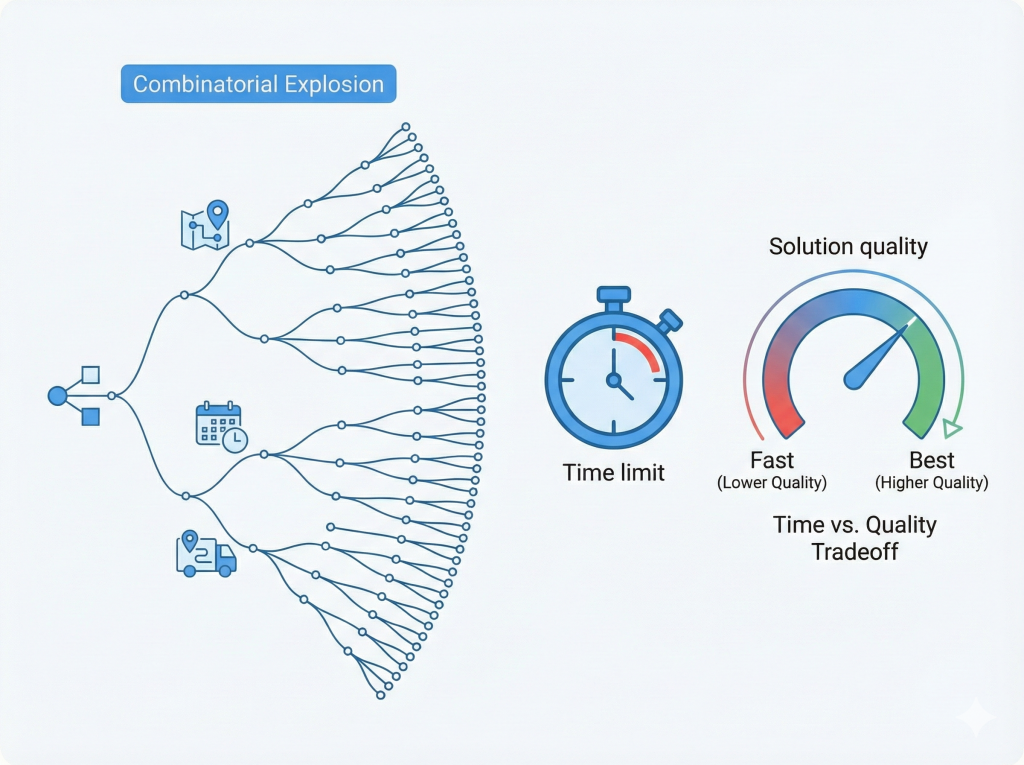

Quantum optimization becomes interesting only when classical optimization hits a real ceiling and the problem has a structure that can map well to binary formulations.

Typical “quantum optimization” target areas

- Routing and logistics

- vehicle routing with time windows, capacity, priorities, and frequent replanning

- last-mile delivery constraints, dynamic orders, disruption handling

- Scheduling

- workforce scheduling with legal, contractual, and fairness constraints

- production scheduling with sequence-dependent setup times

- airline or facility scheduling with many hard rules and penalties

- Portfolio optimization

- discrete constraints: cardinality limits, transaction lots, sector caps

- multi-objective tradeoffs: return vs risk vs constraints

- Energy systems

- unit commitment and dispatch planning

- grid congestion management and constrained planning

What “help” would actually mean

Quantum computing optimization only matters if it improves at least one of these in a measurable way:

- better solution quality under the same time budget

- similar quality but much faster replanning

- more consistent quality across hard instances

- improved exploration of difficult landscapes (fewer “stuck in a local minimum” outcomes)

And even then, most near-term value is expected from hybrid quantum-classical optimization, not quantum replacing classical solvers.

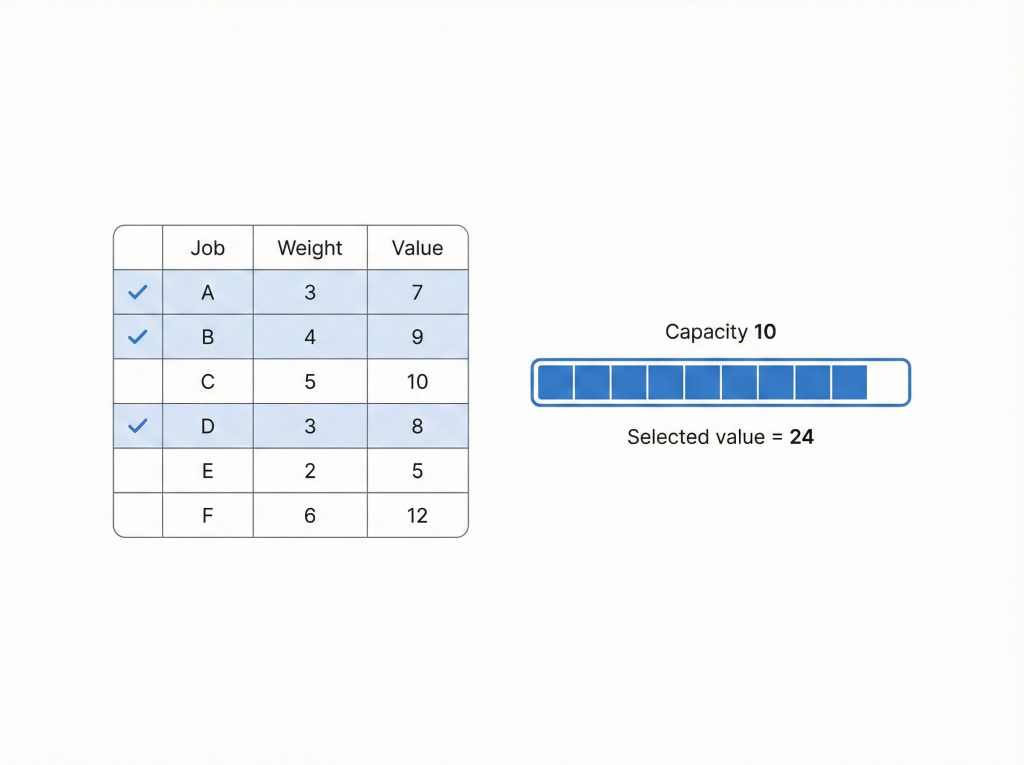

A simple example with numbers (short and clear)

Problem: select jobs to maximize value under a capacity limit

You have capacity 10 (time, space, or budget units). Each job has a “weight” (capacity usage) and a “value” (profit). You choose a subset.

| Job | Weight | Value |

|---|---|---|

| A | 2 | 6 |

| B | 3 | 8 |

| C | 4 | 9 |

| D | 5 | 10 |

| E | 6 | 12 |

| F | 7 | 14 |

Goal: maximize total value without exceeding capacity 10.

One best solution is:

- A + B + D

- Total weight = 2 + 3 + 5 = 10

- Total value = 6 + 8 + 10 = 24 ✅

Other feasible combinations are worse:

- E + C → weight 10, value 21

- F + A → weight 9, value 20

- D + C → weight 9, value 19

Why this relates to quantum optimization:

Each decision is binary (take job or not). That fits the style of problems quantum optimization often targets. In a real business setting, you’d add extra constraints (time windows, dependencies, penalties), which makes the search landscape harder and more “rugged.” That is the scenario where people explore QUBO/quantum annealing or QAOA-like approaches to generate high-quality candidates quickly, then validate and repair classically.

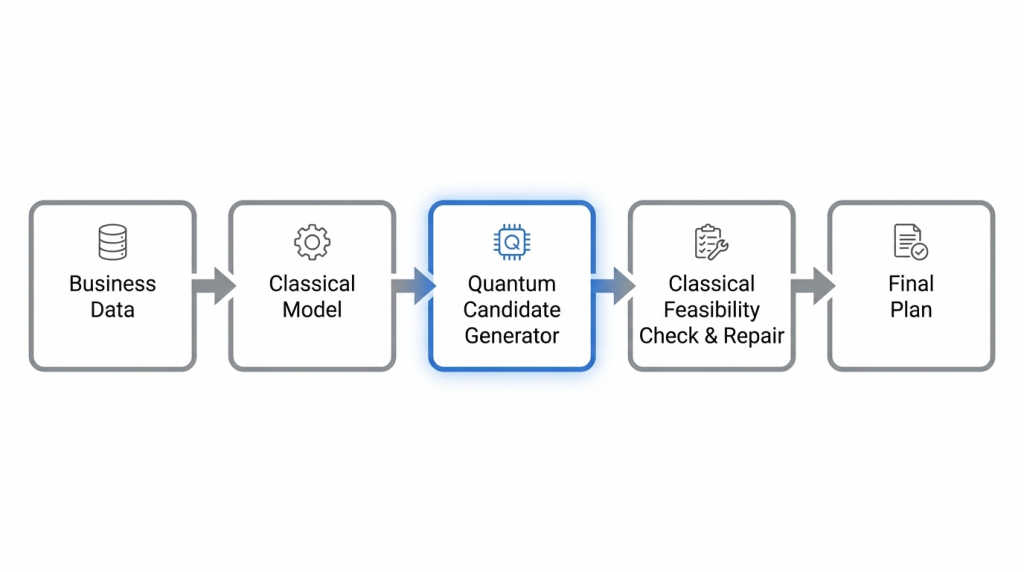

How quantum optimization is used in practice (hybrid workflow)

In most realistic deployments, quantum is not the full optimizer. A practical hybrid workflow looks like this:

- Model the business objective and constraints (classical)

- Extract a hard core subproblem (binary decisions that matter most)

- Use quantum optimization to propose candidates (QUBO/Ising or gate-based methods)

- Classical feasibility check and repair

- Classical local improvement (heuristics/MILP polishing)

- Operationalize (monitoring, retraining/tuning, KPI tracking)

This framing matters for decision-makers: you measure success by KPIs (cost, delay, utilization, service level), not by where the computation ran.

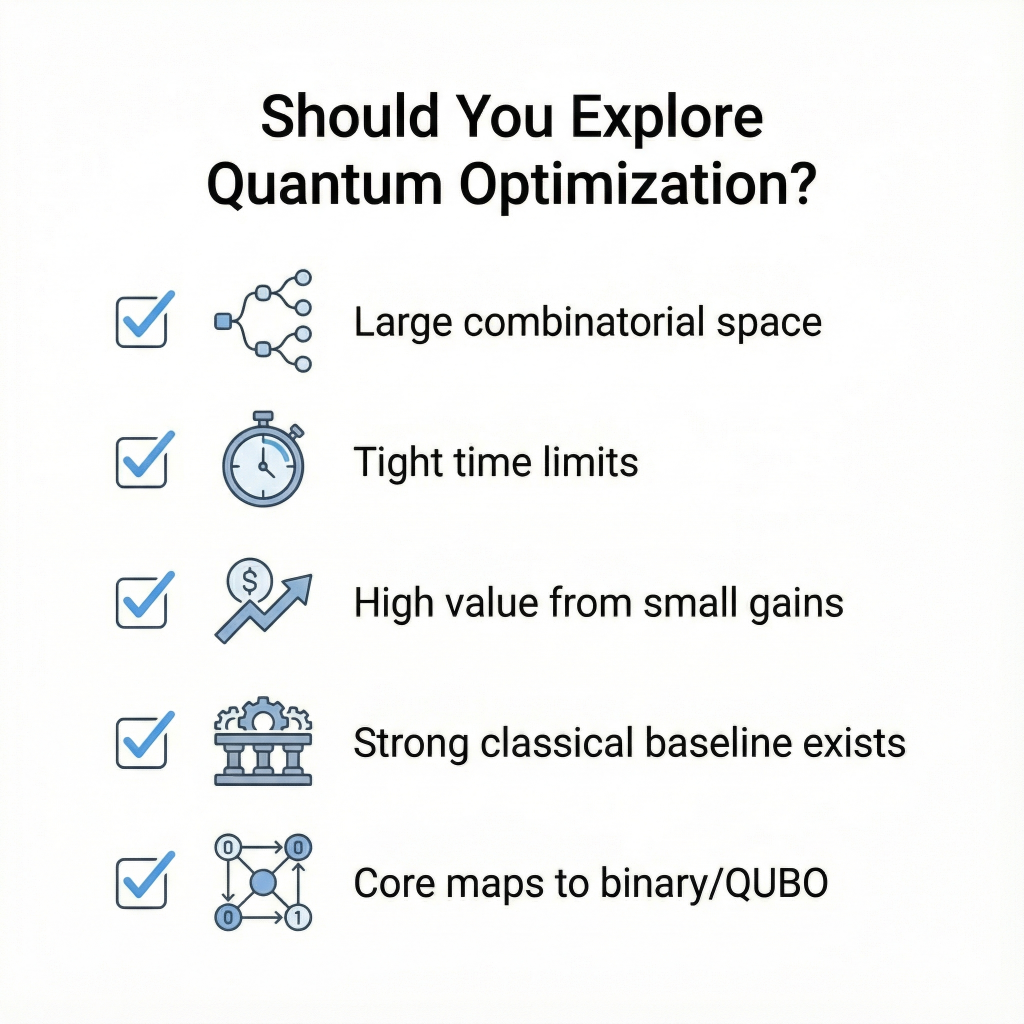

When to explore quantum optimization (decision checklist)

Quantum optimization is worth testing when most of these are true:

- Hard combinatorial structure: the search space explodes with problem size.

- Time pressure: you need solutions fast (frequent replanning, near real-time).

- Classical baseline is strong but still insufficient: MILP/CP/heuristics are already tuned and still miss KPIs.

- Small gains are valuable: even 0.5%–2% improvement matters financially.

- Binary formulation is meaningful: the core can map to QUBO/Ising without breaking the business logic.

- You can run controlled comparisons: identical data, constraints, time budget, and KPIs.

If you cannot meet these conditions, classical optimization improvements usually outperform quantum experimentation.

Quantum optimization is not a general replacement for classical computing. Classical optimization (MILP, CP, heuristics) already solves many business problems efficiently and reliably. Quantum computing optimization becomes interesting when you face genuinely hard combinatorial problems, tight time budgets, and meaningful value from small improvements. The most realistic near-term approach is hybrid optimization: quantum as a candidate engine, classical for feasibility and final performance.